Honored to have this personal essay showcased on AndBloom – such a positive platform – thank you Dee for your support & inspiration!

From Stillness to Flight: On Beauty at Sixty

Honored to have this personal essay showcased on AndBloom – such a positive platform – thank you Dee for your support & inspiration!

From Stillness to Flight: On Beauty at Sixty

…her heart is full and hollow

Like a cactus tree

While she’s so busy being free

―Joni Mitchell, Cactus Tree

This is what I remember.

The sun flashing sharp reflections like splintered glass from the windows of the brick school building. Blue gowns―the dull sheen of row after row of blue polyester blend―not quite navy, not quite royal―rendered nearly beautiful for a moment by a faint ripple of wind through the assembly. A felt banner patterned with our school’s logo draped across the bottom of the stage, the mascot embroidered in one corner, a cougar caught mid-roar.

I sat next to the boy who’d taken me to Senior Prom, a riverboat cruise down the wide Connecticut river, the night muggy and mosquito-filled. We hadn’t spoken since. Not a love match, but no hard feelings. We were both quiet. He’d occupied the desk just behind me in homeroom for four years, and was seated now in the metal folding chair to my right, because our last names began with the same letter. He wore faded sneakers, the suede and stripes worn down from hours on the trails running cross-country. His blond hair curled around the edges of his cap.

A screech of feedback burst from the mic as the principal adjusted for sound. My scalp itched from the bobby pins I’d dug into my long hair to hold the stiff cap in place. A trickle of sweat bled down from behind my ear into the hollow of my collarbone. I fanned myself with the mimeographed program and swiped a cherry Bonne Bell lip balm across my mouth.

Beneath the gown I wore a white boatneck blouse, a Kelly-green linen pencil skirt and navy espadrilles, a tiny pearl stud dotting each earlobe. In the weeks leading up to the ceremony, I’d committed to a strict diet of Fresca, apples and Wheat Thins, supplemented with a piece of dry toast now and then. I felt hollowed out, ready for something new to fill me. A forced bud not quite able to bloom. I touched the bones of my hips and their sharp edges reassured me of my solidity.

That spring we spent afternoons at a friend’s aboveground pool―laying out, as we called it then―slathered in Johnson’s Baby Oil in our high-cut one-piece swimsuits, turning ourselves on the hour like chickens roasting on a spit. Sipping iced tea and smoking Virginia Slims. Then―just when we thought we couldn’t take it any longer―that slow deliberate dive into the blue haven of cool water. Where beneath the surface I could forget the world, college in the fall, the dates I might or might not have over the summer, if I’d ever be as thin and pretty as Olivia Newton John. If I’d ever fall in love.

Who I would be.

I didn’t think about grades or teachers. My SAT scores were high in English, passable in Math. My Advanced Comp and Music teachers loved me. I hated Algebra and Physics and Chemistry, and they hated me right back. No matter.

I’d spent one of my senior terms as a high school scholar, taking a class on modern poetry at the local university, discovering The Waste Land and the blood beating just beneath Sylvia Plath’s sharp words. I walked in clogs and tartan kilt, my tidy backpack slung over one shoulder along the wide paths crisscrossing the quad between buildings covered in wild swaths of trailing ivy. I watched as the leaves leached from brilliant green to pale yellow and swished crisply beneath my feet, pretending with my quick steps along the slate that I knew where I was going. That I’d closed the distance between the insular walls of my small rural high school and the sophisticated swirl of students and professors at this private New England university. I thought then if I pretended to be someone else for long enough, I would become her. That like the lines of poetry I memorized, she would burn herself into my being like an invisible tattoo.

I remember only snippets of the day, images like a deck of cards shuffled too quickly to see the suits. My English teacher sat in the front row, and nodded to me as I passed on the way to the stage. He’d encouraged me to write, and noted in his slanted cursive hand in my composition journal, Your words are beautiful, but sometimes so sad. When I turned in my textbook at the end of the year, he asked, You’re still majoring in literature, right? We both laughed. There’d been talk in my family about me becoming a doctor, but my brain was wired for syntax and iambic pentameter, the rhythm and wholeness of a perfectly crafted sentence. Trigonometry and the mysteries of the periodic table of elements were beyond my ability to parse, then or now.

I graduated near the top of my class, but I didn’t care. I’d already been accepted to college on early admission months before. The valedictorian spoke, glancing at her notes and then up at the audience over the lip of the podium. I didn’t listen to her words. I was absolutely certain she did not know anything I didn’t know. We’d all been together since middle school―year after year in the same classes and activities―Chorus, Swimming, Tennis, Yearbook. There wasn’t anything anyone could have said that day that would have helped me. No inspirational phrase or wish for a golden future.

For my senior quote, I submitted words pulled from a source unremembered now. Because we long to dance, birds fly; because we want to soar with them, the winds blow; because we long to be the wind, we are anchored to the ground.

Did I throw my cap? I may have, but it’s just as likely, I unstuck the bobby pins, shook out my hair and folded it along with the program and the silken tassel into a neat square the size of a small purse. I unzipped the top of the gown and let the breeze cool my throat, my linen skirt fluttering against my bare legs as I stood. I remember thinking I wanted to take off my shoes and let myself feel the green grass under my bare feet.

Then, if I recall correctly―and it’s possible I don’t―the school band played a clumsy anthem as we emptied our seats in a slow procession down the center aisle back to the gymnasium. I was hungry and wanted a cigarette. I let the voices dip and flow around me, the loneliness born of my disdain like a cramped tunnel with no outlet, surrounded by an undulating sea of blue waves.

This is the last time I’ll ever be here, I thought.

If I stepped through an invisible door that day, I don’t remember recognizing it then. The noise level rose as my classmates gathered their belongings from the bleachers, signed yearbooks and slapped each other on the back. I heard well wishes and laughter, the bleat of car horns fading outside.

I was at the end of something and the beginning of something else. But I didn’t know what. I only knew as I stood in line to pass in my gown, I was already gone.

Stepping through the double doors into the hot parking lot, I surveyed the tennis courts where I’d won and lost matches that didn’t mean anything wavering in the heat off the pavement. The brick building rising up behind me. A dropped program already covered with the stamp of footprints on the concrete walkway.

I didn’t say goodbye to anyone. I lowered my sunglasses and made my way to where my family stood at our old station wagon.

Let’s go, I said.

And just like that, in the careless brutal way of teenagers who can only see the moment they are in―not the past, or the terrible, wonderful unknown future―I waved one hand as if to make it all disappear. Four years of my life. Over and done.

I can’t wait to get out of here, I thought, feeling the rush of air on my face through the lowered car window as a cluster of blue and gold balloons that had broken free floated into the June sky.

Congratulations, Graduates! announced the sign at the school entrance. By tomorrow it would gone.

And so would I.

It starts with a wad of bubblegum the summer I turn eight.

Though too young to understand the significance of the four students killed at Kent State or the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, I’m enamored by the Beatles Let It Be playing on our Technics turntable every night when my father returns home from work.

“Put the needle back to the start,” he yells from the living room sofa. “Carefully!”

I crouch at the stereo console, buoyed by this new responsibility. My braids tap against my chest as I lower the plexiglass cover and music fills the room.

One night I chew three sugary squares of Bazooka while reading Nancy Drew with a flashlight under my white summer coverlet. I’m breaking two rules: reading after nine p.m. lights out and chewing gum after I’ve brushed my teeth. I fall asleep with The Hidden Staircase in my hand.

When I wake, the flashlight has burned out and the book is closed beneath the sheet. I’ve entirely forgotten about the bubblegum. After splashing my face with water, I decide to redo my braids. When I get to the top of the first one, my hair pulls against my scalp. I turn sideways towards the mirror. A wad of dried-up pinkish gum is matted in the hair of both braids, and no matter how hard I tug, it won’t come out. I dunk my head under the tap to see if water will help. It does not.

Now I must tell my mother.

She tries to remove the gum with a wide-toothed plastic comb, to no avail. “We’ll go to the salon and have Pat take care of it,” she says.

I sit in the tall swivel chair with a pink plastic drape around my shoulders. Pat swings the chair around so she can work on me. Then she hands me two braids, caramel sprinkled with gold.

“You’re going to love your new hair,” she announces, turning the chair back to the mirror.

“A pixie cut,” my mother quips. “Like Twiggy.”

They both laugh. I can’t believe the person in the mirror is me. When I hop off the chair, the braids fall onto the floor with the rest of my hair.

At home, I run into the bathroom, lock the door and stare at myself in the mirror. My mother’s friend stops by for a cup of coffee. When I come into the kitchen, she says, “Oh, she looks like a little boy.” My mother doesn’t say anything.

I dart into the laundry room, hot tears on my cheeks. I want to go back to who I was before. I want to throw something at my mother’s friend. Instead, I sit on a warm pile of folded towels for a while, then make my way out the side door to the yard.

Up in my treehouse, I can’t see myself. I run my hands through my shorn hair.

A little boy.

In that moment, hidden in the dense leafy branches of the old maple, I decide.

From now on, I’ll be a tomboy like Becky in Huckleberry Finn and Jo in Little Women. I don’t yet know about Amelia Earhart or Joan of Arc, but I will. I have a lot of reading to do while my hair grows back.

Shine until tomorrow, as the song goes.

The first time I open the lid of the giant box blocking my writing road, the inside of the box is dark. I can’t tell if the box is empty or something is hidden at the bottom that I cannot see. A rush of a dark breath touches my face as a whisper brushes my ear, almost too quiet to hear.

You can’t write, she says.

If I could see her face, her mouth would be pulled into a tight sneer of contempt, like a rough line scrawled through a string of letters. As her words enter my body, I grow smaller and smaller. My voice disappears. I become nothing.

For a long time I leave the box sitting in the road. I walk around it―tiptoe, in fact― climbing over rocks and dirt to keep going. But I can still hear her voice like a black river trickling poison beneath the other voices telling me to write: the voices of my characters, classmates, teachers and other writers, my family and friends.

I write over the voice. Because I must, though I don’t know why. I let the words burn through me even when I don’t know where they come from. But secretly I still believe her. I push her voice away, but I’m too afraid to push with all my strength. I’m not accustomed to destroying things.

This time when I open the box, I close my eyes. I wait for her voice. Fainter now than the first time. It doesn’t fill the box. It barely has the strength to rise into my ears.

The weight of my words has silenced the voice. Thousands and thousands of words strung like white lights on tree branches. The jumble of my letters falls into the empty box and fills it to the top. I can barely close the lid. Now the box is mine, and my mind is full of my own words.

The box floats above the road and disappears into the darkening sky, absorbed into the vastness of the universe. My words scatter among the stars.

The road is clear.

You could say the blueprint of my life is captured in an old photograph of us taken in 1964, when I was not yet two years old. My love of books, words on the page, of reading and pictures and stories. I am entirely unaware of the camera at the moment of its capture. I’m too busy listening and memorizing the string of sounds as you translate for me, Fun with Dick and Jane, and the antics of their spirited black and white spaniel, Spot.

We sit at the table in the breakfast nook of your parent’s kitchen on Overlook Avenue, in the house where you grew up. You are a young doctor in your tweed jacket and thick black horn-rimmed spectacles. Thin and angular, well over six feet, you tower over me like a god. The part in your hair is as resolute as the cut of a sharp knife. Your tapered fingers hold the book open on your knees. I occupy a spot on your lap, chubby hands clasped formally, as if I’m a Victorian matron receiving visitors. I wear a smocked short-sleeved dress, white anklets trimmed in lace and a pair of red leather brogues with a strap across my foot. One of my earliest memories is walking in those crimson shoes through puddles on the slate walk to your parent’s front door, iridescent rings like rainbows dissolving under my small feet.

You have spent many years of study in the U.S. and abroad to earn your medical degree. Soon we will move into a new house with a converted barn in the back which will become your office. You will remain a family doctor well into your 80s, ministering to elementary school children and their parents, grandmothers who bring you Italian butter cookies at the holidays, high school boys on the football field at the height of their strength skirmishing on cold Friday nights while you watch from the sidelines with your black bag. Over the course of your career, you will see thousands of patients, perched on the black swiveling stool in your exam room, a folded stethoscope dangling from one pocket, your penlight in the other.

Sometimes I pay you a visit in the office on your afternoon lunch break. I line up flat wooden tongue depressors and long swabs tipped in cotton, listening to your heart under your white coat with the stethoscope hooked over my ears. I never tire of playing nurse to your doctor, tapping your knee with the rubber reflex hammer. I trace the swirling M and D on the pocket of your coat. Open and close the sliding metal drawers, touching gauze pads, rolls of tape, and the sterile instruments laid neatly on the steel tray near your examination table with my sticky child’s hands. When we leave, I swipe a cherry lollipop with chocolate in the center from the glass jar on your secretary’s desk. You touch the top of my head and say goodbye.

Later, you put me to work, studying, reading, and playing the piano. I am a child on a mission, to please you and excel, to be smart like you, accomplished. Not only are you a former basketball star, but you also golf well, and regularly best your opponents on the tennis court. Then there is the piano. Even now, I can recall the melodies of specific passages of your favorite Beethoven and Mozart sonatas, the crashing of notes, long glissandos, your beautiful fingers sliding over the keys. Too fast for my eyes to follow, or my small clumsy hands to imitate.

You sent me to weekly lessons the year I started Kindergarten with a silver-haired Russian émigré, Mrs. Adèle Cohen, who would teach me for the next fifteen years in her tidy living room, surrounded by Persian rugs and lace antimacassars. At my first recital, you stood at the back of that same room as I rushed through My Little Birch Canoe, and played it through to the end without a mistake. When I was in grade school―before you left for evening rounds at the hospital―you would fall asleep in the big velvet chair in the living room as I practiced my Hanon exercises and scales. Whenever I tried to slip off the bench for a snack, you’d wake for a moment, and say “Again.” Because of you, I became a better pianist than I was born to be. In the dire absence of perfect technique, I made use of my diminutive hands to play with emotion. I learned to allow my soul to pass into my fingertips so no one would notice the skipped notes and errors of precision.

I lived in your shadow―learning, observing, refining my mind―until it disappeared.

But all that is almost half a century past.

I made the fitful transition to living in our house without you, your converted office in the barn shuttered, the long parade of patients up the driveway ended. The notes of Bach’s Prelude in C filled an empty room. Junior high and high school were as difficult and lonely as they were somehow supposed to be. Then the years of my young adulthood, when I lost my way, relocating on the other side of the country to begin again. Not in our small town where everyone knew me as the doctor’s daughter, but as myself. I got married and no longer bore your name. Gave birth to two children of my own―one who loves to read, the other to make music.

You and I drifted apart, then gently back together again like the tides of two distant seas. We both grew older and suffered losses from which we could not recover. When I hear your voice now on the phone, it does not remind me of who we were, but of who we have become.

At that long ago kitchen table, your finger tracing the words of the story, we did not know what was to come. Your father poured from a stainless steel coffee pot into a white cup rimmed with a thin red stripe. The bluebird at the feeder squawked through the picture window, scattering seeds on the walk. I felt the scratchy tweed of your coat against the bare skin of my arms, but did not care, did not raise my hand to itch. I inhaled the smell of your hair cream and citrus aftershave lotion. Closing my eyes for a moment as your words slid past and the story unfurled, I imagined a dog like Spot with a glossy coat of fur I could brush again and again.

“Daddy, turn the page,” I commanded, from my perch high on your lap.

I wanted to see what would happen next.

I wanted you to tell me how the story ended.

It started with an Olivetti― my first typewriter as an eleven-year-old―and a stack of clean white onionskin paper. When I sat down at my desk, the click of the keys made it official. I was no longer filling my journal with trivial notations about clothes and boy-girl parties and what my science teacher had to say about my lack of interest in geology.

I was writing.

Poems, stories and the 6th grade play. Once I began, I never stopped. A memoir, two novels, poetry, short stories and essays from middle school through college, in the slim borders between marriage and children and jobs.

I am not a former Prom Queen. I was the quiet smart girl with the black marbled composition book, writing tortured poetry and wearing a beret with a cigarette dangling from the corner of my mouth. But I was also the girl who wanted to belong somehow to a tribe―without changing who I was. I held the same wish we all share: to be known and understood for who we truly are.

Writing is my key to that door. The world of words. The naming of things. My place in the world.

Here I will chronicle my creative life, moment to moment, in a blend of memoir, fiction, poetry and inspiration. I will tell you the things I really want to say the way I want to say them. And share what I can about what I have discovered. Day-to-day, in the moment. Observing and recording, bearing witness.

The Bitter and the Sweet brings together a hopeful patchwork of words and images, memories and quotes. The journey of making art while life―with its rough edges and joyful mysteries―happens around me, unfolding like a lotus flower from the mud.

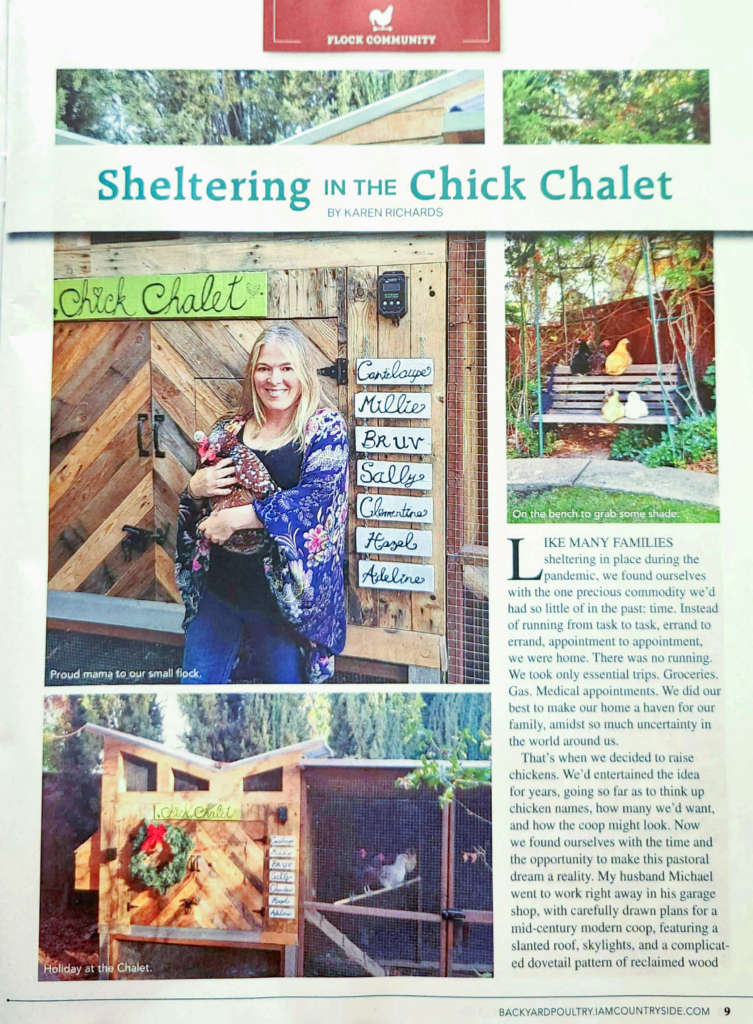

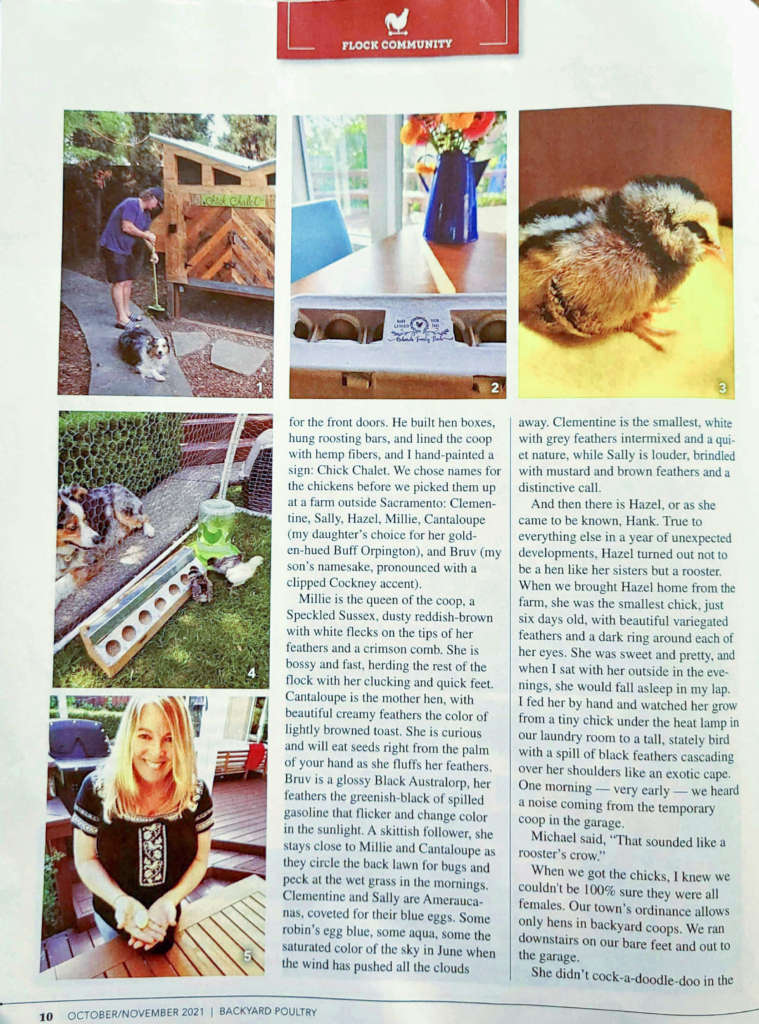

Recently published excerpt from my memoir, You Are Here, about our journey raising heirloom chickens during the pandemic. (From Backyard Poultry Magazine, October/November 2021)

In my favorite photograph of you, you’re looking over one shoulder from the driver’s seat of a pale lemon Karmann Ghia. Your dark hair floats around your face in the bouffant style made popular in the early 60s by Jackie Kennedy. I imagine its loosened waves blowing from the open window as you wind along the one-lane roads of Northern Ireland to the coast. Your blue eyes are the color of the Sea of Cortez, half a continent away. A half-smile hovers on your lips, as if you know a secret you will not reveal. Though I know now the precise circumstances of this moment of your life were quite different, I choose to believe in the story told by the brilliant coral polish on your fingertips around the steering wheel and the jaunty tilt of your head.

They tell me you are going somewhere. The rest of your life has yet to happen.

I am not yet born, and you have not yet crossed the wild Atlantic, made the weeklong sea journey to arrive in America and step down the gangplank in New York City into your new life as a young married woman, with one child not yet beginning to walk and two glossy black steamer trunks layered with Irish linens and wedding china. You are still a smiling girl with an impossibly small waist, the white of your skin as fine as the petals of a lily. On the weekends, you laugh and dance with your suited dates, careful of the stiff corsage at your wrist, your pristine white-gloved hands. You speak four languages and wear a university scarf carelessly draped around your neck as you leave your parent’s house, stepping in high heels into nights filled with stars and music, into the singular moment of your beauty and youth.

Sixty years later, you drive a dove grey Mini Cooper, your silver hair a glimmering halo around your face.

I still hear the lost accents of your voice in my dreams. Call to mind the years we spent together, as you raised three more children, married the love of your life when I was a teen, the many nights we debated art and literature, sat together in darkened theatres watching French films with subtitles, as I passed from child to woman under your care. The hours in the car back and forth to piano lessons and yearly July trips to the shingled cottage on Long Island Sound. When you stood at the kitchen counter to read the first poem I wrote as an awkward twelve-year-old, typed letter by letter on a manual Olivetti typewriter. The sound my tortoiseshell hairbrush made when in a fit of teenage rage I threw it against the closed oak door as you left my room. Evenings on the porch with iced teas and menthol cigarettes, the sound of crickets rising from the damp grass as the pink wash of late summer sky shifted to black. When we said goodbye on the front steps of your colonial house the week before I moved to California to repeat your emigration story, and start my own new life away from everything I’d known.

I will never know who I would have been without you.

You live in me and in my children in ways not always visible. The echo of your shy smile as I bend over the pages of a book. The determined toss of my head in departing one place and moving towards the next. The way my daughter leaves the driveway with a vroom in her own red Mini. Your blue eyes set into her face. My son’s gentle voice, the hushed music of his laughter. My words, flowing like a ribbon of road through the countryside in the hills outside Belfast.

Your yellow car, improbable and rare, full of bright unaccountable hope.

I hear the swift slap of your shoes retreating on the stairs,

The rattle of plates on the draining board as you slam the door;

I pound my fists into the carpet, gulping air.

You drive into the city for a drink; I lie weeping on the floor.

When you swept the coins from the littered dresser top,

An arc of silver dimes rained on the bed.

The children’s whispers in the hallway made us stop;

I bit my lip and gathered coins instead.

Now in the shuttered silence as you sleep,

My throat grows tight. I remember when we lay,

Your breath in my mouth, our hearts’ twin beat;

We never thought it would end up this way.

Tonight, I close my eyes against this sorrow;

We will make it right again, tomorrow.

Twenty-five years later, it occurs to me: Memory is not a gift, but an instrument of delicate torture.

Under a colorless late May sky, I wander through the old cemetery, irises wilting in cellophane under the crook of my arm. Heat rises from the pavement through the soles of my shoes. Headstones slowly waver, rows of marble angels hovering in the weighted air. It will rain tonight, if there is any mercy.

I wore black today for duty. This dress holds the scent of a perfume I wore years ago, the fabric suffused with gardenia. Then, I wore it to attract, to throw a cloak of mystery over my passage through a crowd. Now, I want to slide into a room without preamble, like a shadow under a closed door.

I recall that old expression of Mim’s, “Everything changes, and everything stays the same.”

The path I walk winds up a hill I do not remember. This place is not the place I have played out in my head for twenty-five years. Back in California, I had been naïve enough to believe a cemetery first viewed through a scrim of tears when I was eight years old, would remain burnt into my memory. My body retains of that morning only the churning in my stomach, my mother’s hushed voice, the collar of the velvet dress too tight around my neck ― not these leaning trees, dark birds slowly wheeling in the air, this manicured too-green grass.

White stones repeat themselves, with different names: Gordon, Rivers, St. Clare, Miller. All beloved. All remembered by someone. I cannot find our family plot, the two stones marking my own beloved, inscriptions long memorized: Anton Jozef Novak. 1901-1970. John Christopher Stone. 1960-1980. No stone at all for my tiny lost one.

As I bend to read the name on a flat gravestone, a rivulet of sweat courses down my temple to my lips, salt spreading on my tongue. The gold cross taps the hollow of my throat. My head throbs in the heat. I long for the cool sting of tears against my hot cheeks. Under this sky again, I feel pinned to the earth. I close my eyes, but nothing comes. I raise my wrist up to my mouth in an old gesture, ridges of scar tissue against my parted lips.

I lean back against an angel with folded hands, her kind, weathered face tilted as if listening to an invisible speaker.

This is the day the Lord hath made; let us rejoice and be glad.

Learn more