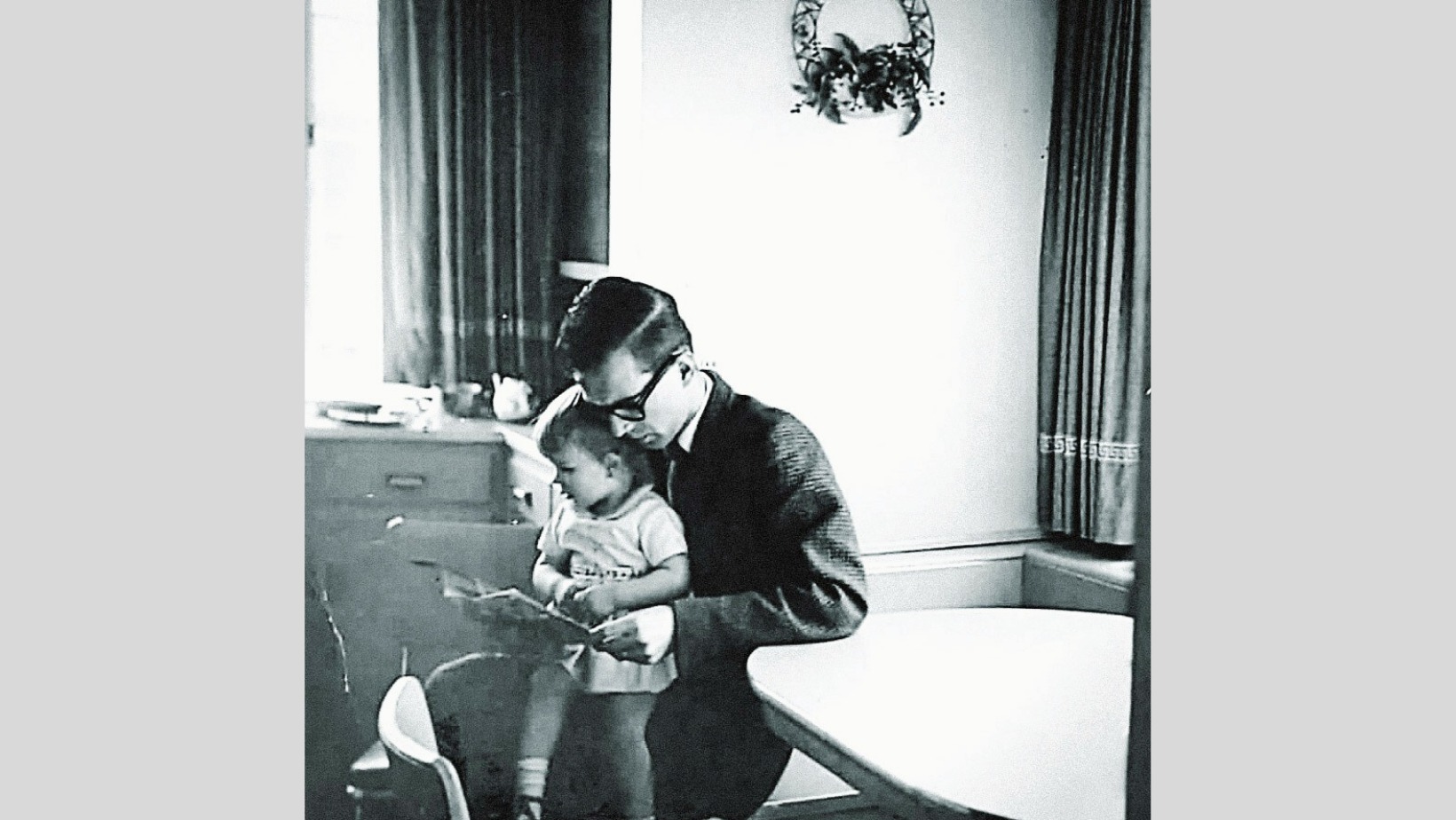

You could say the blueprint of my life is captured in an old photograph of us taken in 1964, when I was not yet two years old. My love of books, words on the page, of reading and pictures and stories. I am entirely unaware of the camera at the moment of its capture. I’m too busy listening and memorizing the string of sounds as you translate for me, Fun with Dick and Jane, and the antics of their spirited black and white spaniel, Spot.

We sit at the table in the breakfast nook of your parent’s kitchen on Overlook Avenue, in the house where you grew up. You are a young doctor in your tweed jacket and thick black horn-rimmed spectacles. Thin and angular, well over six feet, you tower over me like a god. The part in your hair is as resolute as the cut of a sharp knife. Your tapered fingers hold the book open on your knees. I occupy a spot on your lap, chubby hands clasped formally, as if I’m a Victorian matron receiving visitors. I wear a smocked short-sleeved dress, white anklets trimmed in lace and a pair of red leather brogues with a strap across my foot. One of my earliest memories is walking in those crimson shoes through puddles on the slate walk to your parent’s front door, iridescent rings like rainbows dissolving under my small feet.

You have spent many years of study in the U.S. and abroad to earn your medical degree. Soon we will move into a new house with a converted barn in the back which will become your office. You will remain a family doctor well into your 80s, ministering to elementary school children and their parents, grandmothers who bring you Italian butter cookies at the holidays, high school boys on the football field at the height of their strength skirmishing on cold Friday nights while you watch from the sidelines with your black bag. Over the course of your career, you will see thousands of patients, perched on the black swiveling stool in your exam room, a folded stethoscope dangling from one pocket, your penlight in the other.

Sometimes I pay you a visit in the office on your afternoon lunch break. I line up flat wooden tongue depressors and long swabs tipped in cotton, listening to your heart under your white coat with the stethoscope hooked over my ears. I never tire of playing nurse to your doctor, tapping your knee with the rubber reflex hammer. I trace the swirling M and D on the pocket of your coat. Open and close the sliding metal drawers, touching gauze pads, rolls of tape, and the sterile instruments laid neatly on the steel tray near your examination table with my sticky child’s hands. When we leave, I swipe a cherry lollipop with chocolate in the center from the glass jar on your secretary’s desk. You touch the top of my head and say goodbye.

Later, you put me to work, studying, reading, and playing the piano. I am a child on a mission, to please you and excel, to be smart like you, accomplished. Not only are you a former basketball star, but you also golf well, and regularly best your opponents on the tennis court. Then there is the piano. Even now, I can recall the melodies of specific passages of your favorite Beethoven and Mozart sonatas, the crashing of notes, long glissandos, your beautiful fingers sliding over the keys. Too fast for my eyes to follow, or my small clumsy hands to imitate.

You sent me to weekly lessons the year I started Kindergarten with a silver-haired Russian émigré, Mrs. Adèle Cohen, who would teach me for the next fifteen years in her tidy living room, surrounded by Persian rugs and lace antimacassars. At my first recital, you stood at the back of that same room as I rushed through My Little Birch Canoe, and played it through to the end without a mistake. When I was in grade school―before you left for evening rounds at the hospital―you would fall asleep in the big velvet chair in the living room as I practiced my Hanon exercises and scales. Whenever I tried to slip off the bench for a snack, you’d wake for a moment, and say “Again.” Because of you, I became a better pianist than I was born to be. In the dire absence of perfect technique, I made use of my diminutive hands to play with emotion. I learned to allow my soul to pass into my fingertips so no one would notice the skipped notes and errors of precision.

I lived in your shadow―learning, observing, refining my mind―until it disappeared.

But all that is almost half a century past.

I made the fitful transition to living in our house without you, your converted office in the barn shuttered, the long parade of patients up the driveway ended. The notes of Bach’s Prelude in C filled an empty room. Junior high and high school were as difficult and lonely as they were somehow supposed to be. Then the years of my young adulthood, when I lost my way, relocating on the other side of the country to begin again. Not in our small town where everyone knew me as the doctor’s daughter, but as myself. I got married and no longer bore your name. Gave birth to two children of my own―one who loves to read, the other to make music.

You and I drifted apart, then gently back together again like the tides of two distant seas. We both grew older and suffered losses from which we could not recover. When I hear your voice now on the phone, it does not remind me of who we were, but of who we have become.

At that long ago kitchen table, your finger tracing the words of the story, we did not know what was to come. Your father poured from a stainless steel coffee pot into a white cup rimmed with a thin red stripe. The bluebird at the feeder squawked through the picture window, scattering seeds on the walk. I felt the scratchy tweed of your coat against the bare skin of my arms, but did not care, did not raise my hand to itch. I inhaled the smell of your hair cream and citrus aftershave lotion. Closing my eyes for a moment as your words slid past and the story unfurled, I imagined a dog like Spot with a glossy coat of fur I could brush again and again.

“Daddy, turn the page,” I commanded, from my perch high on your lap.

I wanted to see what would happen next.

I wanted you to tell me how the story ended.