Twenty-five years later, it occurs to me: Memory is not a gift, but an instrument of delicate torture.

Under a colorless late May sky, I wander through the old cemetery, irises wilting in cellophane under the crook of my arm. Heat rises from the pavement through the soles of my shoes. Headstones slowly waver, rows of marble angels hovering in the weighted air. It will rain tonight, if there is any mercy.

I wore black today for duty. This dress holds the scent of a perfume I wore years ago, the fabric suffused with gardenia. Then, I wore it to attract, to throw a cloak of mystery over my passage through a crowd. Now, I want to slide into a room without preamble, like a shadow under a closed door.

I recall that old expression of Mim’s, “Everything changes, and everything stays the same.”

The path I walk winds up a hill I do not remember. This place is not the place I have played out in my head for twenty-five years. Back in California, I had been naïve enough to believe a cemetery first viewed through a scrim of tears when I was eight years old, would remain burnt into my memory. My body retains of that morning only the churning in my stomach, my mother’s hushed voice, the collar of the velvet dress too tight around my neck ― not these leaning trees, dark birds slowly wheeling in the air, this manicured too-green grass.

White stones repeat themselves, with different names: Gordon, Rivers, St. Clare, Miller. All beloved. All remembered by someone. I cannot find our family plot, the two stones marking my own beloved, inscriptions long memorized: Anton Jozef Novak. 1901-1970. John Christopher Stone. 1960-1980. No stone at all for my tiny lost one.

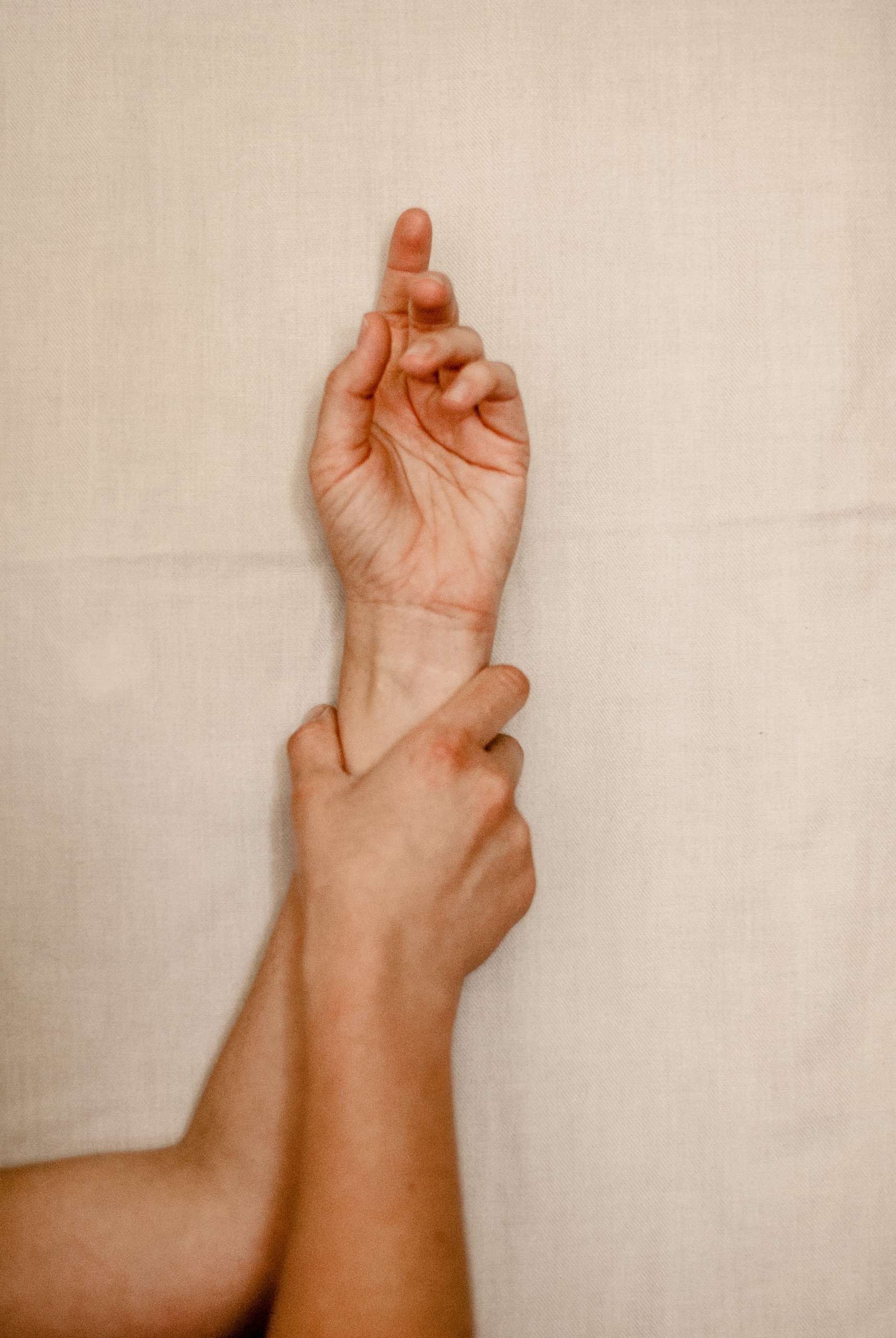

As I bend to read the name on a flat gravestone, a rivulet of sweat courses down my temple to my lips, salt spreading on my tongue. The gold cross taps the hollow of my throat. My head throbs in the heat. I long for the cool sting of tears against my hot cheeks. Under this sky again, I feel pinned to the earth. I close my eyes, but nothing comes. I raise my wrist up to my mouth in an old gesture, ridges of scar tissue against my parted lips.

I lean back against an angel with folded hands, her kind, weathered face tilted as if listening to an invisible speaker.

This is the day the Lord hath made; let us rejoice and be glad.

****

I navigated the rental car down Rowan Street and up the long drive to the old house, avoiding the branches of yellow forsythia in full bloom. Aunt Helen must have heard the car wheels on the gravel. When I pulled into the carport, she came running down the wide steps ― a Hallmark card greeting ― arms flung open, a genuine smile, her whole body arched to fill the space between us. She has held the elegant beauty Mim lost when the drinking took over and began its slow erasure. Thin and tall and neat as a pin. Aunt Helen, our family spinster.

For years, she has been my only true ally in the family, other than Brendan. My father was lost in his artist’s world of paint and canvas long before I left. Sarah, the golden girl, aligned herself with Mim early on. I gave Aunt Helen my address in California and from time to time, she sends me clippings: photographic exhibits coming to the West Coast, Fiestaware, Arts and Crafts furniture, stained glass. She takes care to keep the articles business-related. She sends nothing on forgiveness, estrangement, alcoholism, depression, suicide, abortion, infidelity or death. This is her oblique way of slowly coaxing me open, like a tightly shut razor clam lowered gently into warm water.

When I was a teenager, she used to leave small wrapped gifts outside my locked door: a fruit-flavored lip-gloss, Seventeen magazine, a candle that smelled like freshly cut pine boughs when I burned it. She never knocked. She simply left the gifts in silence and walked away quickly, as if I was a wounded animal. Offerings. I never told her how I looked forward to the early morning hours of darkness, kneeling to take up her gifts before locking the heavy oak door again.

She ran down the steps, calling my name. “Lily! You’re here!” It’s been years since anyone said my name with that exclamation of mingled joy and concern.

I stood by the rental car in my slept-in clothes and sunglasses. The house, a restored Victorian, once owned by a gentleman farmer, seemed much smaller than in memories and dreams. Even Aunt Helen seemed smaller, insubstantial. I recalled other scenes in this driveway: playing with colored chalk and Dales in the shade of the big tree, watching John fly through the air over a skateboard ramp, impossibly landing on his feet, the twins riding their first bikes, matching blue and pink Schwinn’s with training wheels on either side, and later, kissing boys in cars while my father stood behind the front door at curfew waiting for me to come in, flicking the porch light on and off.

“Hey,” I said, still holding the door handle.

“Oh, Lily, you look so different.” She put her hands up to my head, where my long hair used to be. “Your hair,” she sighed, but didn’t continue.

I miss the weight of my hair on my back like a lost limb. Now it’s short and choppy, pieces falling to cover my face. My sacrifice. Gutting my own beauty for a mere idea.

I stepped back, banging my shoulder on the car frame, out of her reach.

She stood with her hands at her sides. “Let me have a look at you.” She was welcome to look. I just didn’t want to be touched. Unwashed hair, my black clothes covered with lint and dust from the red-eye, muscles twitching from all those hours in the airline seat. I wondered if she could smell the beer on my breath.

“You look tired,” she said, rubbing her hands together. And then, like mothers greeting prodigal sons and daughters all over the world, she asked, “Can I fix you something to eat?”

I almost laughed out loud. No, I thought, but you can fix me a drink. “Some breakfast would be nice.” I knew that would keep her busy, not looking too closely at me. We walked into the house, the garnet Persian runner in the hall, older and more worn, the same Danish modern couches flanking the picture window, the old-fashioned TV console, the cherrywood cocktail cart still missing one wheel stationed next to Mim’s leather chair. Nothing had changed.

Aunt Helen went back through to the kitchen, calling, “Just make yourself comfortable.”

As a matter of fact, I will, I thought, kneeling at the cocktail cart over a bottle of Mim’s Grey Goose with about two fingers’ worth in the bottom. I didn’t bother to go into the kitchen for a glass. Aunt Helen would have asked me what I wanted to drink and offered me an orange juice. I tipped the bottle back and felt the burn, familiar and soothing in my throat. Now, that feels like home.

By the time Aunt Helen returned to the living room, I was perched on the edge of the couch, flipping through a two-year-old copy of National Geographic.

“Maybe after you eat, we can take a ride over to the hospital. See your mother. It’s been so long.” She spoke carefully, keeping her voice flat and smooth.

“Does she know I’m here?”

“I think so. I think Brendan told her yesterday you were flying in to Connecticut.” Aunt Helen held the muscles of her face still.

“And?”

“I’m sure she’d want you to visit. Regardless of the past. None of that matters now.” I knew we were both thinking of the baby, all those years ago, lost to the past Aunt Helen wanted all of us to forget. She rushed to fill the silence. “Oh, honey, she looks just awful. It’s so hard for me to watch her deteriorate. We don’t even look like sisters anymore.” She wiped her hands down the front of her half-apron.

“Is she any worse? Dad’s been keeping me in the loop since January, you know.”

“The cancer has spread. Now, there’s nothing to do but wait.”

“She can’t have a liver transplant?”

“Her doctors say she’s not a candidate. It’s just a matter of time and of keeping her comfortable. That’s what her doctors tell us.”

I kept turning over the pages of the magazine as we spoke. Lost tribes of New Guinea. Galapagos Island turtles. The amazing people of Tibet. Anywhere but this room. That’s where I want to be. “So,” I paused and took a breath, “did she ask for me?”

“She only found out yesterday you were coming home.” Even Aunt Helen calls this place home and she hasn’t lived here in thirty years.

“You just said that.”

“Truth is, honey, I’m not sure. But I know if you went in there, you could mend fences. If you only just saw her.”

“You’re saying she doesn’t want to see me? Did she tell you that?”

“That isn’t it ― she’s on a lot of medication.”

“Jesus Christ, she would rather die in that fucking hospital before she’d ever give me a break. She’s on her deathbed, but it’s still Fuck Lily. Christ almighty.” I slammed the magazine onto the table and Aunt Helen jumped at the sound, as if I had slapped her. I smelled burning toast in the air. “You’d better go get that,” I said, gesturing towards the kitchen.

She turned slowly at the door. “You’d have more pity if you saw her, Lily.”

*****

Everyone I ever loved is dead or lost to me or too far away to touch. They are all gone and I am left, rooted here. I read somewhere the life expectancy of an average woman now reaches into her eighties. I can’t imagine remembering all this in my bones for the next fifty or so years. The funny thing is when these things were happening to me ― I didn’t think they were permanent. Part of my history forever. In spite of everything, I believed all wounds could be healed, what was broken could be made whole again, that time would let me finally, gratefully, forget. But it is not so. I need only pull up the sleeves of my dress, to remember.

I think of my scars as letters I sent to myself long ago, missives from another country. The ridges are still raised, but the redness disappeared after a few years, as if my body absorbed the anger back into itself. Without knowing I do so ― sometimes when I am deep in concentration over a tricky bit of restoration ― I find my fingers worrying the places on my forearms, like a tongue endlessly playing over a painful tooth, unable to keep itself away from the tender spot.

They are only white lines now. The fading runes of a forgotten language. The tiny unreadable hieroglyphics of my former self.

*****