…her heart is full and hollow

Like a cactus tree

While she’s so busy being free

―Joni Mitchell, Cactus Tree

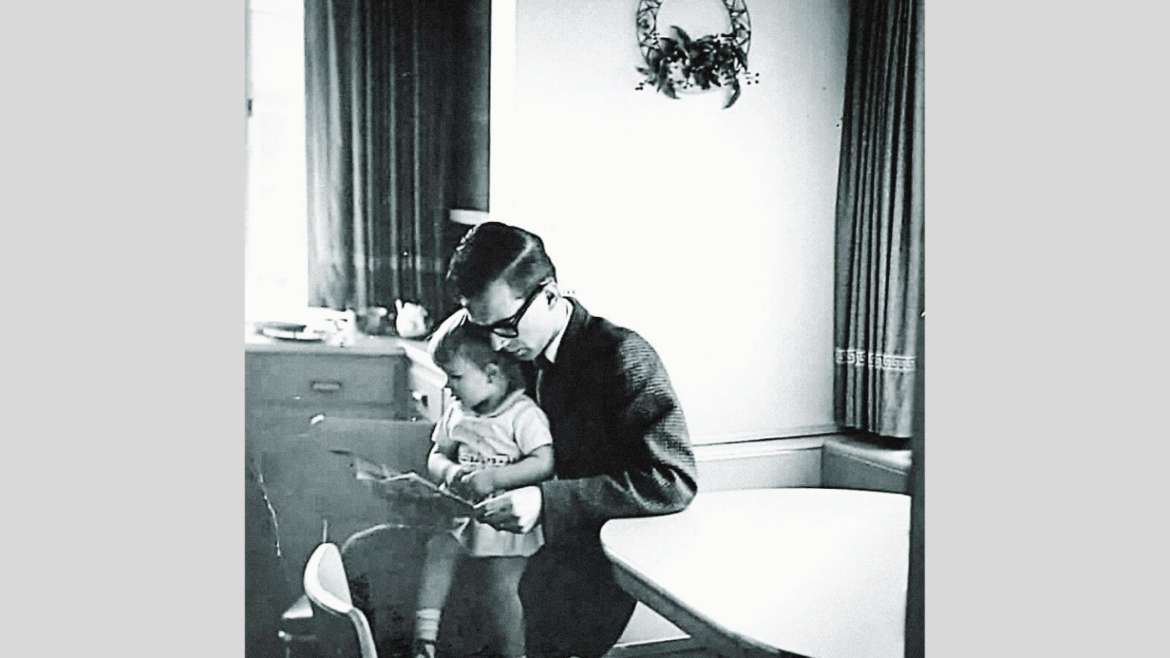

This is what I remember.

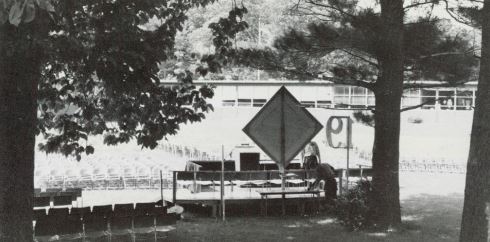

The sun flashing sharp reflections like splintered glass from the windows of the brick school building. Blue gowns―the dull sheen of row after row of blue polyester blend―not quite navy, not quite royal―rendered nearly beautiful for a moment by a faint ripple of wind through the assembly. A felt banner patterned with our school’s logo draped across the bottom of the stage, the mascot embroidered in one corner, a cougar caught mid-roar.

I sat next to the boy who’d taken me to Senior Prom, a riverboat cruise down the wide Connecticut river, the night muggy and mosquito-filled. We hadn’t spoken since. Not a love match, but no hard feelings. We were both quiet. He’d occupied the desk just behind me in homeroom for four years, and was seated now in the metal folding chair to my right, because our last names began with the same letter. He wore faded sneakers, the suede and stripes worn down from hours on the trails running cross-country. His blond hair curled around the edges of his cap.

A screech of feedback burst from the mic as the principal adjusted for sound. My scalp itched from the bobby pins I’d dug into my long hair to hold the stiff cap in place. A trickle of sweat bled down from behind my ear into the hollow of my collarbone. I fanned myself with the mimeographed program and swiped a cherry Bonne Bell lip balm across my mouth.

Beneath the gown I wore a white boatneck blouse, a Kelly-green linen pencil skirt and navy espadrilles, a tiny pearl stud dotting each earlobe. In the weeks leading up to the ceremony, I’d committed to a strict diet of Fresca, apples and Wheat Thins, supplemented with a piece of dry toast now and then. I felt hollowed out, ready for something new to fill me. A forced bud not quite able to bloom. I touched the bones of my hips and their sharp edges reassured me of my solidity.

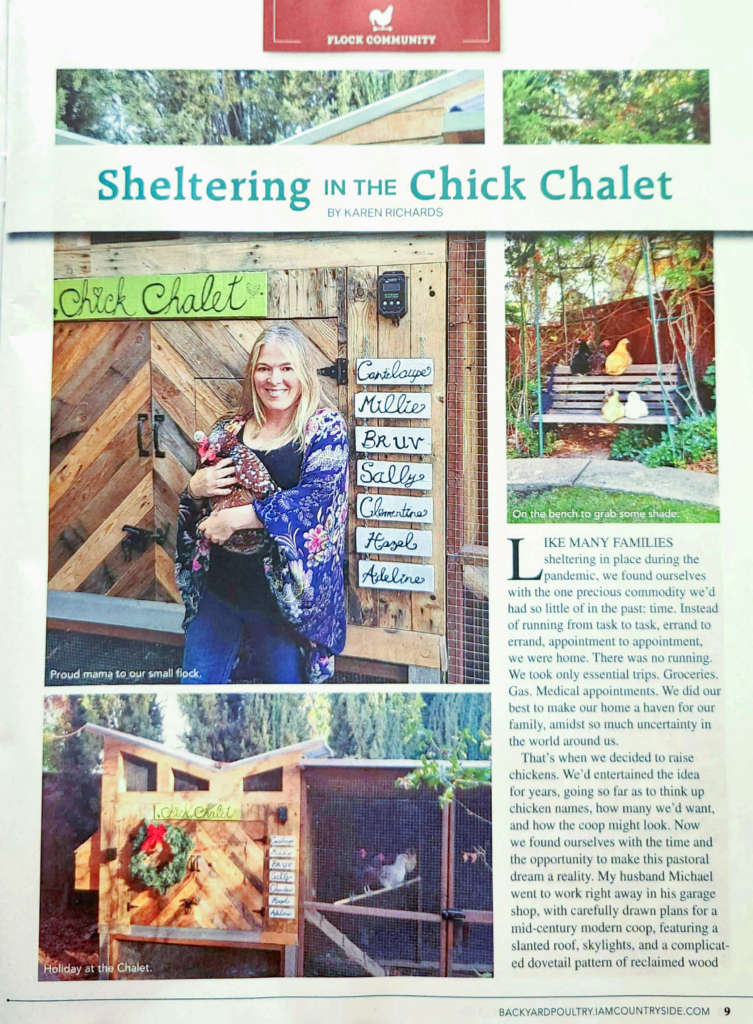

That spring we spent afternoons at a friend’s aboveground pool―laying out, as we called it then―slathered in Johnson’s Baby Oil in our high-cut one-piece swimsuits, turning ourselves on the hour like chickens roasting on a spit. Sipping iced tea and smoking Virginia Slims. Then―just when we thought we couldn’t take it any longer―that slow deliberate dive into the blue haven of cool water. Where beneath the surface I could forget the world, college in the fall, the dates I might or might not have over the summer, if I’d ever be as thin and pretty as Olivia Newton John. If I’d ever fall in love.

Who I would be.

I didn’t think about grades or teachers. My SAT scores were high in English, passable in Math. My Advanced Comp and Music teachers loved me. I hated Algebra and Physics and Chemistry, and they hated me right back. No matter.

I’d spent one of my senior terms as a high school scholar, taking a class on modern poetry at the local university, discovering The Waste Land and the blood beating just beneath Sylvia Plath’s sharp words. I walked in clogs and tartan kilt, my tidy backpack slung over one shoulder along the wide paths crisscrossing the quad between buildings covered in wild swaths of trailing ivy. I watched as the leaves leached from brilliant green to pale yellow and swished crisply beneath my feet, pretending with my quick steps along the slate that I knew where I was going. That I’d closed the distance between the insular walls of my small rural high school and the sophisticated swirl of students and professors at this private New England university. I thought then if I pretended to be someone else for long enough, I would become her. That like the lines of poetry I memorized, she would burn herself into my being like an invisible tattoo.

I remember only snippets of the day, images like a deck of cards shuffled too quickly to see the suits. My English teacher sat in the front row, and nodded to me as I passed on the way to the stage. He’d encouraged me to write, and noted in his slanted cursive hand in my composition journal, Your words are beautiful, but sometimes so sad. When I turned in my textbook at the end of the year, he asked, You’re still majoring in literature, right? We both laughed. There’d been talk in my family about me becoming a doctor, but my brain was wired for syntax and iambic pentameter, the rhythm and wholeness of a perfectly crafted sentence. Trigonometry and the mysteries of the periodic table of elements were beyond my ability to parse, then or now.

I graduated near the top of my class, but I didn’t care. I’d already been accepted to college on early admission months before. The valedictorian spoke, glancing at her notes and then up at the audience over the lip of the podium. I didn’t listen to her words. I was absolutely certain she did not know anything I didn’t know. We’d all been together since middle school―year after year in the same classes and activities―Chorus, Swimming, Tennis, Yearbook. There wasn’t anything anyone could have said that day that would have helped me. No inspirational phrase or wish for a golden future.

For my senior quote, I submitted words pulled from a source unremembered now. Because we long to dance, birds fly; because we want to soar with them, the winds blow; because we long to be the wind, we are anchored to the ground.

Did I throw my cap? I may have, but it’s just as likely, I unstuck the bobby pins, shook out my hair and folded it along with the program and the silken tassel into a neat square the size of a small purse. I unzipped the top of the gown and let the breeze cool my throat, my linen skirt fluttering against my bare legs as I stood. I remember thinking I wanted to take off my shoes and let myself feel the green grass under my bare feet.

Then, if I recall correctly―and it’s possible I don’t―the school band played a clumsy anthem as we emptied our seats in a slow procession down the center aisle back to the gymnasium. I was hungry and wanted a cigarette. I let the voices dip and flow around me, the loneliness born of my disdain like a cramped tunnel with no outlet, surrounded by an undulating sea of blue waves.

This is the last time I’ll ever be here, I thought.

If I stepped through an invisible door that day, I don’t remember recognizing it then. The noise level rose as my classmates gathered their belongings from the bleachers, signed yearbooks and slapped each other on the back. I heard well wishes and laughter, the bleat of car horns fading outside.

I was at the end of something and the beginning of something else. But I didn’t know what. I only knew as I stood in line to pass in my gown, I was already gone.

Stepping through the double doors into the hot parking lot, I surveyed the tennis courts where I’d won and lost matches that didn’t mean anything wavering in the heat off the pavement. The brick building rising up behind me. A dropped program already covered with the stamp of footprints on the concrete walkway.

I didn’t say goodbye to anyone. I lowered my sunglasses and made my way to where my family stood at our old station wagon.

Let’s go, I said.

And just like that, in the careless brutal way of teenagers who can only see the moment they are in―not the past, or the terrible, wonderful unknown future―I waved one hand as if to make it all disappear. Four years of my life. Over and done.

I can’t wait to get out of here, I thought, feeling the rush of air on my face through the lowered car window as a cluster of blue and gold balloons that had broken free floated into the June sky.

Congratulations, Graduates! announced the sign at the school entrance. By tomorrow it would gone.

And so would I.